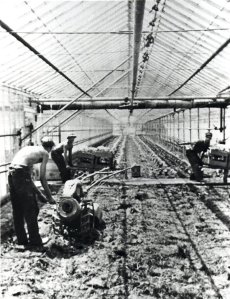

Youngstown Depression Relief Gardens, 1932.

The Great Depression struck the the United States at the end of 1929 and lasted until 1939. This economic disaster affected the economy of the entire world and put hundreds of thousands out of work and in serious financial trouble. City government, realizing the seriousness of the situation, put relief gardening programs in place to combat hunger, poverty, and emotional stress (Williamson). These relief gardens, also called welfare garden plots, vacant lot gardens, and subsistence gardens, served the same purpose as the potato patches of the 1890’s: they improved the health and spirit of participants by creating feelings of usefulness, productivity, and importance while also providing opportunities for food and work. (Tucker 1993)

There were three phases of gardening programs during the Great Depression. In the beginning the relief garden movement faced many problems. Organizers argued about the size and and make-up of gardens: Should the gardens have individual plots or larger undivided plots? Who should be involved? Where will the plots be? Many wondered if the depression would even last long enough for the relief gardens to be necessary. Those asking for assistance were no long the disable, sick, and elderly, but the unemployed and desperate, many with families. No longer was it the ‘weakness’ of the individual that caused the need for assistance, this time it was the failure of the ‘system’ (Warman 1999). During these early years ordinary citizens were incredibly helpful in supporting gardening programs. For example, in Detroit “city employees donated monthly contributions from their salaries to raise the ten thousand dollars necessary for financing a free garden program” (Tucker 1993: 132).

Hard at work in Youngstown Depression Gardens, 1932

These disagreements and organizational challenges hindered the program in its beginning years, but were resolved by 1933. By this time, non-governmental organizations such as the Family Welfare Society and the Employment Relief Commission formed garden committees to help combat hunger. Those with land of their own were encouraged to cultivate it instead of taking up valuable gardening space in the overflowing relief gardens. Seeds and supplies were provided for those working the gardens. Many farmers disliked the welfare garden program, thinking that it maintained the economic depression by adding to the overproduction already taking place (Warman 1999).

Relief Gardens helped the Beuscher family survive in Iowa during the Depression

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt became the president of the United States bringing with him his “New Deal.” Over the next three years, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) gave over three billion dollars of aid in their work garden program. Gardeners received a wage for cultivating and distributing produce to those in need. These gardeners, however, had to meet strict eligibility requirements to participate. The work garden program shifted relief gardens from being for anyone in need to being jobs for some. This program lasted until 1935. An addition to the federal gardening program individual gardening programs continued cities around the country. In New York City, a gardening campaign led by the welfare department and helped by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), resulted in the formulation of over 5,000 gardens in vacant lots (Warner 1987). These 5,000 gardens produced $5 worth of vegetables for every dollar invested resulting in a total of $2.8 million worth of food by 1934 (Tucker 1993).

Clarke Bennert tilling an urban greenhouse

Image from Columbia Historical Society, Inc

In 1935 the government cut funding for relief gardening programs because they were no longer viewed as as opportunities for success and improvement of life. After this remarkably successful period of relief gardening, these urban kitchen gardens returned to their initial view as a method of coping with poverty for those who were lazy, disabled or elderly. Their named shifted from relief gardens to welfare gardens, giving them a much more pitiful connotation. However, the country’s experience with the success of relief gardens in the early 1930’s made them much more open to the idea of victory gardens in World War II (Bassett 1981).

References for Relief Gardens

Warman, Dena Sacha. 1999.Community Gardens: A Tool for Community Building. Senior Honours Essay, University of Waterloo. http://www.cityfarmer.org/waterlooCG.html#2.

Gardenmosaics.org. History of Community Gardens in the U.S. http://www.gardenmosaics.cornell.edu/pgs/science/english/pdfs/historycg_science_page.pdf

Williamson, Erin A. A Deeper Ecology: Community Gardens in the Urban Environment. U Delaware. http://www.cityfarmer.org/erin.html

Really great paper found of the City Farmer website, it has great background and history and incite into the need for and role of community gardens in North America.

Lawson, Laura. 2005. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America. University of California Press.

Tucker, David M. Kitchen Gardening in America: A History. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1993.

Warner, Sam Bass, Jr. To Dwell is to Garden: A History of Boston’s Community Gardens. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987.

Wikipedia. The Great Depression in the United States. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression_in_the_United_States

Five Families in Dubuque: The Urban Depression 1937-1938. 2003. University of Northern Iowa. http://www.uni.edu/iowahist/Social_Economic/Urban_Depression/urban_depression.htm#Park%20Family%20Interview%20January%201938

Ohio Historical Society. Great Depression Scrapbook-The Country & The City. http://omp.ohiolink.edu/OMP/YourScrapbook?scrapid=31028.

Leave a comment