Petroleum supplies slowly dwindle as demand rapidly soars. So the prices of gasoline and oil that supply modern societies with their industrial production of food will go up, up, and away. A radically different future than the oil-energized twentieth century is dawning.

Let’s face it: our world has become increasingly maddening. Bad news mounts each day: unending wars, financial crises, earthquakes, hurricanes and cyclones killing thousands, chaotic climate change, vanishing pollinating bees and polar bears, rising oceans, thinning forests and a host of human-created or –worsened threats. We live in uncertain times with an even more uncertain future. We face unprecedented, unpredictable converging threats. What can one do to remain somewhat sane? The ostrich approach of denial by burying one’s head in the sand will not be effective or life-enhancing.

It is a good time for an increasing number of people to return to the multiple benefits and pleasures of growing at least part of their own food by gardening and farming. In addition to satisfying the need to eat and drink, farming can also help deal with depression, passivity, and other forms of psychological suffering. It can help treat both the body and the soul.

One of the many good things that farms based on nature’s patterns can do is help balance people. Much psychological suffering and even mental illnesses have to do with imbalances, which characterize modern society. Before turning to drugs, one can at least trying visiting farms and perhaps volunteering to work there. Or one can connect with farms in collaboration with another treatment program.

Farming can be done in ways that preserve the Earth and put humans in direct contact with it. “Small farms are the most productive on earth,” according to the May 11 “New York Times” article “Change We Can Stomach” by farmer and chef Dan Barber. “A four-acre farm in the United States nets, on average, $1,400 per acre; a 1,364-acre farm nets $39 an acre,” he writes. “Farming has the potential to go through the greatest upheaval since the Green Revolution, bringing harvests that are more meaningful, sustainable, and, yes, even more flavorful,” Barber contends.

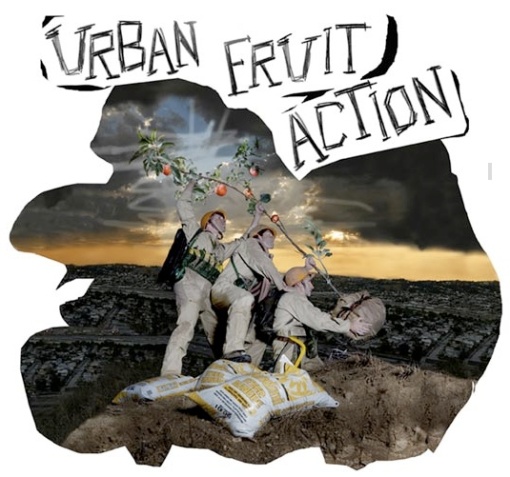

Since growing one’s own food is not possible for everyone, it is also a good time to establish direct relationships with local farmers and shop more at farmers’ markets, farm stands, and by subscribing to Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs). Urban agriculture, farms on the urban fringe, and rooftop gardening are becoming increasingly popular. The large city of Havana, Cuba, grows 70% of its own food. Necessity will change how people get their food in the near future.

Many Americans take their food sources for granted, assuming that super-markets will be able to always supply them with what they need. Having lived in Hawai’i when delivery disruptions and the lack of transportation across the ocean left bare shelves in food stores, I know the panic this can cause.

The “Silent Tsunami,” “Misery Index,” and Mud Cakes

A “silent tsunami” of hunger sweeps the globe, reports the head of the United Nation’s World Food Program, Josette Sheeran, speaking in late April at a food summit in London. The heightened hunger threat endangers 20 million of the world’s poorest children and is pushing 100 million people into poverty.

“This is the new face of hunger—the millions of people who were not in the urgent hunger category six months ago but now are,” Sheeran reports. “The world’s misery index is rising.”

During 2008 food riots broke out in the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. “You are seeing the return of the food riot, one of the oldest forms of collective action,” commented Raj Patel in an April 25San Francisco Chronicle article. The University of California at Berkeley scholar wrote the new book “Stuffed and Starved: Power and the Hidden Battle for the World Food System.”

The World Bank estimates that food prices have risen 83% in three years; other estimates are in the 60 and 70 percent range. Even in the wealthy United States we have recently seen rationing of rice and other staples by food giants such as Costco and Wal-Mart’s Sam’s Clubs, the two biggest warehouse retail chains. Such trends are likely to continue and are creating stockpiling and hoarding.

“In the poorest districts (of Haiti), there is now a brisk trade in mud cakes,” writes Patel in an article titled “The Troubles with Food,”. “Mothers feed the biscuits, made with water, salt, margarine and clay, to their children. The cake puts a dampener on hunger, at least for a couple of hours, but leaves your mouth dry and bitter for several hours more,” he continues.

Industrial agriculture will be one of the many aspects of human life on the planet hit by the dwindle/demand oil trend and the related peaks of other fossil fuels, such as natural gas. Industrial agriculture depends upon petroleum in many ways—to run tractors and other machines, to make chemical pesticides and fertilizers, and to fuel the trucks that transport food an average of 1500 miles from field to fork. Oil is the most important ingredient in most of conventional food. As the dwindle/demand rate intensifies, food will be less available and more expensive. Famine is likely.

Survival will require that more people return to an earlier energy supply— muscle power. As someone who made a transition in the early 1990’s (while in my late 40s) from a livelihood based on college teaching and related intellectual activities to one based on farming, I can report that there are many advantages to such a change. I feel better as a result of living on the land, growing some of my own food, and sharing that organic food and the farm itself with others.

I have found my local place. In 2003 I accepted a great job offer in Hawai’i, but after a couple of wonderful years, I felt so homesick that I returned to my farm.

So this will be a report from the farm front, which will focus on some of the psychological benefits of farming.

The multiple consequences of a diminishing supply of humanity’s major energy source at this point in history will include hardships, stress, and suffering. There are many ways of dealing psychologically with such matters, including with family, friends and professional counselors. This article will explore what I have come to describe as agropsychology and agrotherapy.

I was trained to be a counselor. Quite frankly, I was not good at delivering individual therapy. I got too emotional and involved. I did not adequately develop the necessary professional armor and shield. I did not take enough distance from the people I was working with or have enough “impulse control.” So I shifted more to teaching, group work, and writing. In the time since my more conventional psychological training some forty years ago, self-disclosure and emotional men have become more acceptable as sex roles and professional codes have evolved.

Ecopsychology and Ecotherapy

Sierra Club Books published “Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind” in l996. The term refers to the emerging synthesis of the psychological and the ecological. The book’s editor, Theodore Roszak, writes that “ecology needs psychology, psychology needs ecology.” Roszak reports on a l990 conference entitled “Psychology as if the Whole Earth Mattered.”

The Sierra Club plans to publish the book’s sequel “Ecotherapy: Healing with Nature in Mind” in March of 2009. My chapter “Farming, Sweet Darkness, Poetry, and Healing” is scheduled to be part of that book. After finishing my contribution I began to realize that what I was writing about could be called agrotherapy, which is the practice of agropsychology, which are sub-sets of ecopsychology and ecotherapy. Farms have historically been healing places, for both those who live and work there and those who visit. Farm tours and even overnight farm stays are becoming increasingly popular as examples of ecotourism. The Small Farm Program at the University of California at Davis, Sonoma County Farm Trails, and Daily Acts are among the many groups that promote such tours.

Simply put, by living on a farm and working the land on a regular basis, I have become a healthier person—physically and mentally. In recent years I have been hosting an increasing number of farm tours at Kokopelli Farm in the Sebastopol countryside, Sonoma County, Northern California. Community, school, and religious groups, as well as families and friends, come to the farm, which grows mainly organic berries and fruit and cares for chickens.

My visitors tend to feel better from their time on this traditional farm; something positive usually happens to them. Being outside in nature can benefit people. People typically loose sight of chronological time. They can fall into berry time or chicken time, which tend to be slower than the human-made clock, and often more fun and stress-reducing. They sometimes lose their restraint and order, wanting to sprint ahead, or go off the path, as if they were animals, which they are.

Chicken Wisdom and Agrotherapy

This year I returned to teaching psychology, part-time, at Sonoma State University. I sometimes take chickens as Teaching Assistants (TAs). For example, I took two sweet silkies on Valentine’s Day; they modeled being love birds as they cooed and cuddled, one even feeling safe enough to lay an egg.

Chickens can teach many things, such as surrender to what is, joy at the dawn, transformation of throwaways into jewels, and love of the Earth within which chickens take their dust baths to help them get rid of parasites. Chickens offer incredible eggs, humor, joy, and beauty. That other two-legged can teach chicken wisdom, that of a prey, to humans, who are predators. It includes, but is not limited to, the following: delight in simple things (like worms), keep dancing, recycle, snuggle into the earth, slow down, combine vulnerability and hardiness.

Agrotherapy is not therapy-as-usual. It happens mainly in the open, outside an office, a building, a city and without a defined time limit. The freedom to wonder and to meander characterize being outside. One does not enter the same human-made setting each time; farms are seasonal, as humans are, and are constantly changing. The therapists-of-the-outdoors include trees, berries, birds, bees, chickens, the moon and stars, the clouds, crow congresses and others who can help relieve stress, anxiety, suffering, and even sickness.

Tears sometimes come to the eyes of city folk when they sit on the ground beneath the giant redwoods or sprawling oaks at my farm. Something from their personal or collective memory seems to get activated. We listen to the wind and hear various sounds within it. Within just a few minutes I can usually feel a change in my guests. This is not a “talking cure.” It is non-talking, opening to the other senses. There is not therapeutic couch or chair; the forest provides a comforting bed upon which one can relax and reduce their stress.

My presence on such tours is more as a guide who can point things out, including patterns in nature and persons, and pose strategic questions, than as an expert to make book-based diagnoses and human-devised treatments. Farming—like therapy or personal growth–is a process with no clear beginning or end. There are products along the way, but the topsoil, for example, takes thousands of years to make. Perennial trees and berries planted by one family member can endure far beyond his or her lifetime into that of descendents, continuing to provide beauty and healing.

An email I sent to a local online listserve about agropsychology generated the following response from Jennifer York, the owner of the Bamboo Sorcery outside my hometown of Sebastopol:

“I can vouch for what you call “agropsychology.’ It saved me as a youth in my recovery from a traumatic childhood, and now in middle age. I am once again finding great healing, joy, and contentment in growing my own garden and raising my own farm animals (chickens, rabbits, and someday dairy goats, I hope!) for food, fun and deep connection with the cycles of life and death. For me it is a spiritual, as well as a practical avocation. I recommend it. Besides, it may come in very handy someday.

“In the meantime I am having fun, and feel good about sharing the experience with my 6-year-old daughter. I believe it is creating a sound foundation in her for the future. I have great gratitude to my deceased parents who were Back-to-Landers in the late 60’s and 70’s, and who exposed me to this rich and life affirming way of life.

“My husband says he can tell how happy I am by how much dirt is under my finger nails…and it’s true.”

In his book “Peak Everything: Waking Up to the Century of Declines” Peak Oil theorist Richard Heinberg includes a chapter titled “The Psychology of Peak Oil and Climate Change.” He writes, “The next few decades will be traumatic.” One resource that Heinberg refers to is the work of eco-philosopher Joanna Macy with respect to workshops on “despair and empowerment.” In them people are encouraged to deal with their grief, and thus feel their connection to the Earth.

Ecopsychology and ecotherapy can take many forms, including agropsychology and agrotherapy. These recently conceptualized fields can make a contribution to the larger fields of psychology and psychotherapy and thus to the healing of people and of the nature of which we are an integral part. Humans often seem to battle nature, whereas participation and collaboration with it seem more healthy, which these developing forms can support.

(Dr. Shepherd Bliss, sbliss@hawaii.edu, teaches at Sonoma State University in Northern California and has operated the organic Kokopelli Farm since the early 1990s. He is a member of the Veterans Writing Group (www.vowvop.org), has contributed to two dozen books, and is currently writing “In Praise of Sweet Darkness.”)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Editorial Notes ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Shepherd Bliss is an Energy Bulletin contributor.

Ben Reynolds, one of the authors of the report explains: “We are all familiar with allotments, and the odd community garden as features of the city landscape, but more often than not a lot of space is wasted, where with a little support we could see projects like this in the UK, where salad crops, vegetables and even fish are produced commercially within the city.”

Ben Reynolds, one of the authors of the report explains: “We are all familiar with allotments, and the odd community garden as features of the city landscape, but more often than not a lot of space is wasted, where with a little support we could see projects like this in the UK, where salad crops, vegetables and even fish are produced commercially within the city.”