City Gardens Abound In Cuba, Where 70% Of Vegetables And Herbs Are Local And Organic

HAVANA, June 4, 2008

(CBS/ Reinaldo Gil)

(CBS) This story was written by CBS News producer Portia Siegelbaum in Havana.

“Buy local. Eat seasonal. Eat organic.” All now commonplace admonitions in the United States.

But while none of these slogans are household words in Cuba, 70 percent of the vegetables and herbs grown on the island today are organic and the urban gardens where they are raised are usually within walking distance of those who will consume them. So in one blow Cuba reduced the use of fossil fuels in the production and transportation of food. And they began doing this nearly 20 years ago.

The island nation’s move to organic and sustainable farming did not arise from its environmental consciousness, although there was an element of that also. The main reason was the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, Cuba’s only source of petroleum and main trading partner at that time.

Overnight long lines formed at gas stations that all too often ran out before all their customers could fill up. Traffic was virtually non-existent. Chinese “Flying Pigeon” bicycles replaced both private and public transportation.

“Puestos” as Cubans call the produce section of their rationed grocery stores displayed only empty bins as agriculture ground to a halt. Chemical pesticides and fertilizers vanished. Tractors became relics of a former time. Oxen pulled the plows that furrowed the fields.

Finding food for the dinner table became a day-long drudge. Cubans visibly lost weight. The communist youth daily, Juventud Rebelde, ran articles on edible weeds. Daily caloric intake dropped to about 1600 calories.

Organic agriculture “made its appearance at that moment as a necessity and that necessity helped us to advance, to consolidate and expand more or less uniformly in all 169 municipalities,” says Adolfo Rodriguez. At 62, he is Cuba’s top urban agrarian, with 43 years experience in agriculture.

He says there are now 300,000 people employed directly in urban agriculture without counting those who are raising organic produce in their backyards as part of a State-encouraged grassroots movement. In all, Rodriguez claims nearly a million people are getting their hands dirty organically.

With 76 percent of Cuba’s population of just under 11 million living in cities, the importance of this form of farming cannot be over emphasized, says Rodriguez.

I think that Cuba’s urban agriculture has come to stay.

Adolfo Rodriguez, urban agrarian

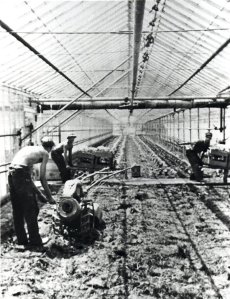

The urban gardens have been dubbed “organoponicos.” Those located in never-developed empty lots primarily consist of raised beds. More complicated are those created in the space left by a collapsed building, not uncommon in cities like Havana where much of the housing is in a very deteriorated state and where all it takes is a heavy tropical rainfall followed by relentless sunshine to bring down a structure.

“We have to truck in the soil,” before anything can be planted, explains Rodriguez. “The basic issue is restoring fertility, the importance of producing compost, organic fertilizers, humus created by worms,” he says.

In a majority of cases the fruits and vegetables are freshly picked every morning and go on sale just with a few feet of where they grew. Only in exceptional cases, such as the densely population municipality of Old Havana (as the colonial section of the capital is named) do the organic fruits and vegetables travel a kilometer or so by a tricycle or horse drawn cart to reach consumers.

Havana residents line up at the organoponico at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which grows a wide variety of vegetables, fruits and herbs. (CBS/Manuel Muniz)

Lucky are the Havana residents who live near the organoponico at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue. Occupying nearly an entire city block, it grows a wide variety of vegetables, fruits and herbs, as well as ornamental plants. It will even sell fresh basil shoots for customers to plant in their own herb garden. On a recent day, customers were offered the following fresh produce at reasonable prices: mangos, plantains, basil, parsley, lettuce, garlic, celery, scallions, collard greens, black beans, watermelon, tomatoes, malanga, spinach and sweet potatoes.

Luckily for Cubans in general, organic here is not equivalent to expensive. Overhead costs are low. The produce is sold from simple aluminum kiosks, signs listing the day’s offer and prices are handmade, electricity is used only for irrigation, and no transportation other than walking from the raised beds to the kiosks is involved. The result? Everything is fresh, local and available.

Convincing Cubans to buy this produce, especially the less familiar vegetables, so as to prepare earth friendly meals, presented a hurdle. The ideal meal on the island includes roast pork, rice and beans and yucca. A lettuce and tomato salad was popular. But the idea of vegetable side dishes or an all vegetarian meal was inconceivable to most.

“We’re cultivating some 40-plus species but you have to know who your customers are,” says Rodriguez. “We can’t plant a lot of broccoli right now because its not going to sell but we’re making progress.” For example, he notes, in the beginning practically no one bought spinach. Now, all the spinach planted is sold. Persuading people to eat carrots, according to Rodriguez, was an uphill battle. “We had to begin supplying them to the daycare centers,” so as to develop a taste for this most common of root vegetables.

The “queen” of the winter crop is lettuce. The spring/summer “queen” is the Chinese string bean. Cuba’s blazing summer sun doesn’t allow for growing produce out of its season, even under cover, except in rare circumstances.

The saving of heritage fruits, vegetables and even animals has also gotten a boost from the urban agrarian movement. The chayote, a fleshy, pear-shaped single-seeded fruit, had virtually disappeared from the market. Now, Rodriguez says, 130 of Cuba’s 169 municipalities are growing the fruit that many remember from their grandmother’s kitchen repertoire in which it was treated as a vegetable, often stuffed and baked.

“We are working to rescue fruit orchards that are in danger of extinction,” stresses Rodriguez. “We’ve planted fields with fruit species that many of today’s children have never even seen, such as the sapote. To save these species we’ve created specialized provincial botanical gardens,” he explains.

Similarly, the urban agrarian movement is rescuing native animal species such as the Creole goat and the cubalaya chicken, the only native Cuban poultry species.

Currently spiraling global food prices are hitting the island hard. Cuba has been importing just over 80 percent of the food consumed domestically. The government is making more land and supplies available to farmers and this may well include chemical fertilizers and pesticides in an attempt to greatly reduce this foreign dependency.

Adolfo Rodriguez, Cuba’s top urban agrarian (CBS/Reinaldo Gil)

Rodriguez does not believe this push to quickly increase agricultural output will negatively impact on the urban organic movement. Even during the 1990s, known in Cuba as the “Special Period,” he says, the potato crop continued to receive chemical pesticides and fertilizers. And even today, the 30 percent of the non-organic produce includes, for example, large-scale plantings of tomatoes for industrial processing.

“I think that Cuba’s urban agriculture has come to stay,” concludes Rodriguez. “That there is a little increase in the application of fertilizers and pesticides for specific crops is normal but that’s not to say that the country is going to shift away from organic farming, to turn our organic gardens into non-organic ones.”

Ben Reynolds, one of the authors of the report explains: “We are all familiar with allotments, and the odd community garden as features of the city landscape, but more often than not a lot of space is wasted, where with a little support we could see projects like this in the UK, where salad crops, vegetables and even fish are produced commercially within the city.”

Ben Reynolds, one of the authors of the report explains: “We are all familiar with allotments, and the odd community garden as features of the city landscape, but more often than not a lot of space is wasted, where with a little support we could see projects like this in the UK, where salad crops, vegetables and even fish are produced commercially within the city.”